There are two factors that must be considered in the design of detention facilities for a new courthouse or for an existing courthouse undergoing renovation: (1) providing security for court staff, judges, courthouse security personnel, attorneys, and the public; and (2) providing detention facilities that properly accommodate defendants. Balancing these factors can sometimes be challenging.

Placing Detention Facilities in Context

Courthouse security is a broad and complex subject. One significant component involves prisoner movement – where law enforcement or court security personnel transport prisoners from a local detention facility to the courthouse for trials or hearings. This movement involves careful coordination and procedures. I’ve described two aspects of this in previous blogs that discuss the critical components of sallyports and prisoner circulation. Two additional components of the prisoner movement process are the stops at the central cellblock and courtroom holding cells, and it’s these requirements that I’ll focus on here.

The courthouse detention facilities and procedures used by many jurisdictions are generally based on the American Correctional Association’s Performance-Based Standards, which address a broad range of considerations such as facility safety codes, emergency preparedness, training, inspections, proper medical treatment, etc. One of the guidelines that directly impacts courthouse planning deals with the physical facility requirements of the detention facilities within the building.

The Central Cellblock

Let’s begin with requirements for the central cellblock. This is the facility where defendants are placed after they are brought to the courthouse and while they are awaiting either a proceeding or transport back to their detention center. In addition to holding cells, the cellblock should ideally support several other functions, including providing space for attorneys to meet with their defendants. In older facilities, the cellblock may not include sufficient space for such meetings.

Attorney-Defendant Meeting Rooms

Several weeks ago, while having lunch with an attorney who practices both civil and criminal law, he described a recent incident in a local Virginia courthouse. While meeting with his client in the cellblock to discuss the upcoming sentencing options, which would include jail time, the client became irate and grabbed him through the bars of the cellblock, tearing his suit jacket before a court security officer could restrain the prisoner.

Like many small and older courthouses, this central cellblock did not have a dedicated attorney-defendant meeting room and, in this instance, the attorney met with his client in the corridor outside of the defendant’s cell, which allowed the defendant easy access to the attorney through the bars of the cell. In a dedicated meeting room, the attorney enters from the public corridor, the prisoner is escorted to the room from within the central cellblock area, and the room is securely divided by bars or break-resistant glass that do not allow any physical contact, as pictured below. Although often overlooked, security for defense attorneys is a critical component of safe central cellblock design and the presence of one could have eliminated my friend’s unfortunate experience.

Attorney-Defendant Meeting Room

Number of Cell and Cell Types

In addition to attorney-defendant meeting rooms, the composition of the actual cellblocks is another important factor in courthouse security. There are very specific architectural, structural, materials, and technical electronic standards designed to provide maximum security for both law enforcement personnel and everyone else in the courthouse. The standards cover everything from stainless steel toilets to electronic cell door locks to CCTV and control systems from a courthouse law enforcement command center. It’s difficult to identify one or two security measures that are more important than the others, especially when considering the range of ingenuity employed by defendants anxious to exploit any weakness in the system.

One story stands out in my mind. During a tour of a historic Oregon courthouse, a security officer described an incident in the building’s antiquated cellblock. As he was attempting to open the door of the cell to escort a prisoner to a trial, the key stuck in the older manual lock. While he was trying to make the key work, the prisoner reached out, grabbed his hand, pulled his arm through the cell bars, and attempted to grab the key ring. Fortunately, a second security officer in an administrative section of the cellblock heard the commotion and helped the first officer regain control. The first officer suffered bruises and a bad sprain, but thanks to the second officer who luckily happened to be nearby, a far more serious security breach was prevented.

This situation could have been avoided altogether if the cellblock had been fitted with electronic door locks controlled by a law enforcement command center.

In addition to security concerns, central cellblock facilities must also be safe for prisoners, offer humane physical conditions, and protect detainee’s statutory and constitutional rights. These factors can be addressed when planning the appropriate number and type of cells, which an experienced courthouse planner will base on existing and projected court caseload.

Although space may become a limiting factor, particularly in a courthouse renovation project, the central cellblock should ideally provide:

- Enough cells to prevent overcrowding

- Group cells to hold defendants being tried together

- Dedicated male defendant cells

- Dedicated and separate female defendant cells

- Dedicated and separate juvenile defendant cells

- Attorney-defendant meeting rooms

Courtroom Holding Cells

Another important part of prisoner movement involves internally transporting defendants from the cellblock to the courtroom. This is where courtroom holding cells come into play. As the name implies, these facilities are located adjacent to courtrooms and are used to house prisoners while awaiting a trial or hearing, or waiting during recesses in proceedings. For both convenience and security, these cells should ideally be located immediately adjacent to the courtroom with direct access into the room. This last point is especially critical to preserve separate circulation paths for the public, judges, and defendants.

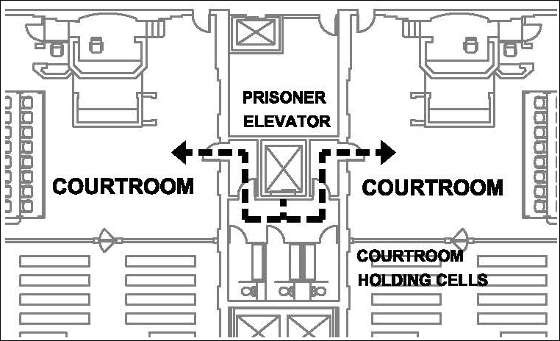

Although most existing courthouses provide one holding cell for each trial courtroom, two holding cells per courtroom, is the preferred number to accommodate multi-defendant trials, male and female defendants, and other situations where two or more defendants are needed in the courtroom. Another configuration that is effective is three holding cells shared between two courtrooms, as shown in the following plan.

Shared Courtroom Holding Cells

While touring a courthouse in Oklahoma, I witnessed the limitations of a single holding cell firsthand. While I was measuring the dimensions of the courtroom during a brief recess in a criminal trial, I was asked to quickly leave the room. I found out later that a male and female defendant were being held together in the single holding cell when the male defendant acted inappropriately towards the female. The court security officers had to act quickly to remove her from the situation and ultimately ended up putting her back in the courtroom, handcuffed to an attorney table.

Another security consideration that can be very helpful in dealing with situation where prisoners do not always behave is an A/V feed between the courtroom and a courtroom holding cell, where an unruly defendant removed from the courtroom can still participate in the proceedings. This also ensures that prisoner rights to trials and hearings are preserved without unnecessary delays.

Conclusion

Providing a safe and secure courthouse for all users is a prime objective of any planning or design effort. Designing secure central cellblocks and courtroom holding cells that also appropriately accommodate defendants is a critical part of this effort.

________________________________________________________________

Our new Courthouse Planning Guide is available NOW!

<<< To get yours, Click Here.

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

-1.jpg)

.jpg)