A new courthouse is a desirable solution for courts that are out of space or live with an aging courthouse that doesn’t easily accommodate changing technologies and processes. Unfortunately, it’s rarely that easy, especially considering that new courthouse construction can cost tens or hundreds of millions of dollars. Fortunately, a new courthouse doesn’t necessarily mean a new building. One solution is revitalizing older commercial or non-court buildings and adapting them as new court facilities. This option for courthouse planning benefits both the government (which doesn’t have to fund an expensive new construction project) and the community.

Advantages of Adaptive Reuse

Repurposing a commercial or other non-court building for court use can benefit many areas. Here are some of those benefits:

For the Court

- Ideally, a courthouse would be situated in a central downtown location, but finding the right place, especially in vibrant urban centers, can be difficult. Reusing an existing building can provide more options for sites that may not have been available for new construction.

- Generally, constructing a new building is more expensive than renovating. So it makes sense that repurposing an existing building, even one not originally designed as a courthouse, could be a cheaper option for the court and potentially save substantial capital costs. Another important cost factor that is often overlooked is the nearby infrastructure. Elements like roads, parking, utilities, emergency services, and public transportation are likely already in place for an existing building, which would lower the overall cost compared to constructing a building in a new location.

For the Community

- In many cases, older vacant or underutilized buildings in a downtown area are landmark structures. Even if they’re not listed on the historic register, they’re still symbols of the origin of the community. However, empty or not fully occupied buildings often fall into a state of disrepair or convey a depressing impression of neglect (if you’ve ever walked through an urban area suffering from an economic downturn, you know what I’m talking about). In cases like this, the ability to preserve and revitalize buildings like these benefits more than just the basic facility. It can refresh an entire area and maintain a visible image of the community’s character.

- Expanding on the point above, empty or even blighted buildings often negatively affect the entire area and can potentially result in decreased tax revenue for the individual building and the surrounding area. In some smaller communities, a few vacant buildings can lead to the eventual demise of the downtown. Revitalizing even one building for a courthouse not only helps the appearance of an entire block but can also have a domino effect, stimulate economic activity, and encourage businesses to relocate to the area.

- One final point about the economic benefits to the community: vacant buildings and urban areas often take on a “ghost town” look as individuals move on to more attractive places. This lack of foot traffic further hurts the site, which is then caught in a downward economic spiral. Without business and commercial activity, nothing entices the public to the area. Nothing can encourage businesses to open or expand if there’s little or no foot traffic in the area. Revitalizing an old building for court use means that there is a rapid growth in the number of people who will be coming to the site daily (court employees, attorneys, potential jurors, and anyone with court business) and who will be looking for restaurants, cafes, and other shops to frequent while they’re downtown. This activity could serve as a quick shot in the arm for the community.

While traveling around the country as a courthouse planner, I have had the opportunity to visit many courthouses that are prime examples of successful adaptive reuse. They represent a broad range of original uses. Here are four of my favorites: a corporate headquarters in Tennessee, a high school in New Mexico, an upscale department store in California, and a railroad station in Washington State.

The Corporate Headquarters: Knoxville, Tennessee

Corporate Headquarters to Courthouse – Knoxville, TN

In 1991, Whittle Communications Corporation, a media company based in Knoxville, Tennessee, began building its corporate headquarters in the center of the downtown. Unfortunately, after spending $56 million on the project, Whittle went out of business before it could occupy the building. The building sat vacant until 1995 when it was purchased for the bargain price of $22 million to be used as a much-needed courthouse. After some renovation, including remodeling the existing structure and adding a new wing with several courtrooms, the new courthouse opened in 1998.

This instance of adaptive reuse proved to be a perfect example of a court/community win-win scenario. The court developed an updated courthouse facility for a fraction of the cost of constructing a new building. The community benefitted by having a fully functioning and busy courthouse located downtown instead of the shell of a building that had sat vacant for several years.

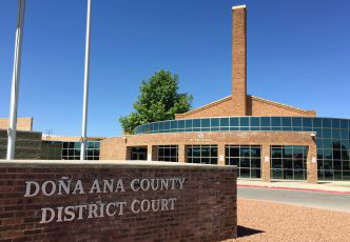

The High School: Las Cruces, New Mexico

High School to Courthouse – Las Cruces, NM

A handsome but unused two-story brick building at the edge of downtown Las Cruces in Dona Anna County, New Mexico, received the gift of a third life as a courthouse thanks to adaptive reuse.

The historic building, a Las Cruces landmark, was originally constructed as the Las Cruces Union High School in 1927. The building was converted to the Alameda Junior High School in 1956 when a new upper school was built to accommodate a growing student population. It again outgrew its usefulness to the school district and was completely shuttered in the early 1980s. Vacant until the mid-1990s, the Dona Anna court considered it a cost-effective solution for accommodating a growing caseload.

The red brick and concrete structure was expanded with two courtroom additions on the east and south sides of the building. The building’s towering brick chimney was retained during renovation and became the centerpiece of the building’s semi-circular glass panel entryway.

In this example of adaptive reuse, a much-loved historic landmark was preserved for the community as a civic use that all could appreciate.

The Upscale Department Store: Santa Barbara, California

Department Store to Courthouse – Santa Barbara, CA

It may seem ironic that a one-time upscale department store was converted into a bankruptcy court, especially since the original commercial and the new courthouse might be considered at opposing ends of the economic spectrum. Yet when the I. Magnin department store in Santa Barbara went bankrupt; this is exactly what happened.

I work with an architect who was a previous Santa Barbara resident and visited the store regularly with his wife. (He said he didn’t mind waiting while she browsed the clothing sections because it allowed him to enjoy the store's unique architectural details, including the central atrium and other well-appointed areas.)

With the 1993 conversion to court use, the court inherited a handsome building and retained many of the original architectural features of the department store. Most importantly, the adaptive reuse continued to support the lively pedestrian activity and high financial viability that downtown Santa Barbara is known for.

The Railroad Station: Tacoma, Washington

Railroad Station to Courthouse – Tacoma, WA

One of the best architectural examples of adaptive reuse I’ve seen is converting the Union Station rail terminal to a courthouse in Tacoma, Washington.

In the late 1980s, the Tacoma court needed to grow beyond its existing facilities. At the same time, the city was pondering what to do with the historic grand Union Passenger Station that opened in 1911 but was abandoned by 1984. By the early 1990s, the court agreed to lease and rehabilitate this beaux-arts landmark.

The existing grand rotunda of the building was renovated into space for two courtrooms, two chambers, and court offices. At the same time, a three-story addition, which housed eight additional courtrooms, chambers, other offices, and detention cell facilities, was constructed. This addition was built in a manner that allowed the existing historic train station to remain visually separate so the addition would not compete with or detract from the splendor of the original building.

This 10-courtroom project resulted in the developing of a highly functional and attractive courthouse that saved a historic railroad station and its famous copper dome from decay and neglect. The court benefited from a reduced initial capital cost, while the community helped by gaining an actively used building that has become a major factor in revitalizing downtown Tacoma.

The great hall beneath the rotunda also serves as a public event space (also available for private event use) and houses a chandelier by world-class glass artist Dale Chihuly. His studio and museum are adjacent to the courthouse, accessible by a pedestrian bridge. The area surrounding the courthouse has become home to two other public museums and an important asset in Tacoma. TripAdvisor lists the courthouse as Tacoma’s 12th most popular tourist site.

Conclusion

Whether it’s getting a prime downtown site for a more-than-reasonable price, renovating a building that’s fallen into disuse, invigorating a downtown area, or saving a piece of local architectural history, these four examples of adaptive reuse show that the advantages of thinking beyond new construction or renovating an existing courthouse can benefit both the court and an entire community. And, as a side benefit, a building with an interesting pedigree and back story is infinitely more fascinating than a building constructed from scratch.

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

-1.jpg)