Objectivity is the bedrock of the American judicial process. We expect the judicial process to be fair and impartial. Should we expect anything less when we plan and design the court facilities that support this process? It’s no surprise that opinions on architecture can be very subjective. From Renaissance to beaux-arts, neo-classical to Art Deco or post-modern, the styles reflect both the subjective trends of the era and the preferences of the individual architect or design team. But is there a way to bring more objectivity into courthouse planning and design? Yes, there is, and it’s through courthouse performance metrics.

My Struggle with Subjectivity

When I was an architectural student, my classmates who provided the most sculptural project designs would frequently get the best grades. Often, I would look at these designs, and while I would agree that they looked terrific, some questions invariably would come to mind. Are all the required spaces actually in the building? Why are there no restrooms on the third floor? Why is the conference room on a different floor than the rest of the office? Does the building meet the operational needs of the occupants? All too often, the answers fell short. The functional needs of the building had been lost in an attempt to provide a great piece of art. What I was looking for, although I didn’t realize it at the time, was an objective approach to assessing the actual quality of a project’s design - one that would balance the importance of the building’s function with its aesthetic appeal.

A few years later, as a court planning consultant responsible for performing needs assessments, I discovered what I had been seeking. I found that using performance metrics to measure how a building meets a court's operational requirements is invaluable in ensuring a more objective courthouse planning process. I'll go ahead and elaborate.

What Are Performance Metrics?

Performance metrics are factors that are used to measure the performance of a building against a set of defined requirements. They are rated on a grading scale (think A through F) based on a clearly defined set of performance criteria. Unlike a report card, if a building meets 90% of a specific area's standard, it gets an A, 80% gets a B, and so on. The grades for each factor can be combined to produce an overall performance score for the building. Weights can also be added to make some factors count more heavily than others in the overall score.

Performance Metrics in Courthouse Planning

In courthouse planning, we typically rate a building in five specific areas: space standards, space functionality, building condition, security, and technology. For courts, the jurisdiction has a set of design guidelines that can be used to generate performance standards. Still, we have often used our database of courthouse performance standards to help a court define its requirements. Once the performance metrics are established and a courthouse is assessed, the results provide the court with a baseline value that quantifies how well the courthouse meets operational needs. Attention can then be focused on addressing the most significant deficiencies in each area.

Performance Metrics Applied

Performance metrics can be applied to several scenarios, including (1) determining the quality of an existing courthouse, (2) evaluating the suitability of design options for a courthouse project, or (3) helping to choose a proposed design for a new courthouse.

Here are examples of each scenario from my personal experience.

(1) Existing Courthouse Needs Assessments

I recently inspected a courthouse where law enforcement moved prisoners to courtrooms through the narrow, restricted judges' corridor (see photo below). The court's initial opinion, before applying performance metrics, was that they needed to reroute the judges’ path of travel to avoid this security nightmare. Redesigning the floor based on this premise would have been costly and a significant disruption to other tenants in the building. However, by conducting a needs assessment using performance metrics, I was able to show that unsecured prisoner circulation was the actual deficiency, not the judges’ circulation.

By highlighting this deficiency through the performance metrics, the court was able to fund a less costly and less disruptive solution of providing a dedicated prisoner elevator and a secure corridor for prisoner movement.

Judges’ Restricted Corridor

Practical facility improvements like the one described in the courthouse security scenario above can often be established by applying performance metrics. Similarly, adjacency issues can be identified through functionality factors, undersized areas through space standards factors, safety compromises through security factors, facility maintenance issues that have gone unnoticed for years through building condition factors, and modern technology requirements through technology factors.

(2) Comparing Design Solutions

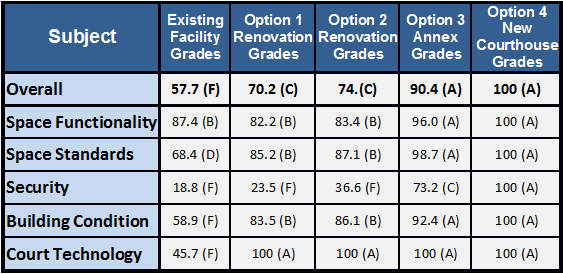

Using performance metrics can also allow a court to make informed decisions about long-term housing strategies. The grades for an existing courthouse can be compared to proposed design solutions to objectively determine the best option for mitigating any deficiencies. This is precisely how I used the comparative courthouse grades spreadsheet shown below. The spreadsheet was developed for a Virginia court considering a wide range of options to solve its existing historic courthouse's space and security needs.

Comparative Courthouse Grades

The performance metrics analysis began with a needs assessment of the existing courthouse. The results—not so good—are shown in the first column (overall failing grade of 57.7). Each design option was then evaluated using identical performance metrics to reflect what the new grades would likely be after each of the strategies was completed. This illustrated the magnitude of improvement that could potentially be realized.

As seen in the spreadsheet, two renovation options, one annex option, and one new courthouse option were considered. While the new courthouse option was the winner, the annex option proved to be a close second. Although I have been involved in projects where design decisions could be immediately made because the performance metrics clearly showed that one design option provided a more beneficial result, this jurisdiction is currently debating both possibilities.

When performance measures such as these are considered along with projected costs for a project, I have helped courts quickly determine which design decision would be most beneficial in an objective and quantifiable way.

In Michigan, I evaluated two renovation strategies for an existing courthouse with very different estimated construction costs. One design option improved the overall assessment grade by 20%, from a D to a B. However, this option would have cost hundreds of thousands of dollars more than another design option that improved the assessment value by 17% - a little less than the first option, but still a grade of B. It was clear by performing this simple cost analysis based on performance metrics that it would be in the court's best interest, as well as in the best interest of the taxpayers, to achieve nearly the same level of benefit for a much smaller price tag.

One exciting thing I have noticed in applying this method is that, in many instances, an emotional attachment to a courthouse makes the court lean toward keeping the existing building, even if it means undertaking a costly renovation. This occurred on a court planning project for a 1930s-era courthouse in Tennessee.

Using performance metrics, I pointed out that the court operations would only be marginally improved from 68% (D level) to 79% (C level) through a renovation project. However, a new courthouse with an assessment grade near 100% (A level) would cost nearly the same amount. Sentimentality aside, it would have been a questionable decision to retain the existing building while only minimally improving court operations.

(3) Comparing New Courthouse Options

I have also used performance metrics in courthouse planning to evaluate new courthouse design options and determine the one that best meets the court's operational needs. This is particularly helpful during the schematic design phase before the project design moves too far along a potentially dysfunctional tangent.

I would even recommend performing periodic performance metrics analyses of a design during the design development and construction document phases to ensure the design remains focused on the court’s full range of objectives.

Courthouses: Beautifully Designed ... and Functional!

Based on my own experiences, I firmly believe that performance metrics mitigate the role of subjectivity in courthouse planning and design.

However, I sometimes admire a stunning piece of architecture that may need to be optimally functional but is sure fun to look at. A courthouse is not the right place to settle for just a beautiful design......it must function well for all who use it, too!

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

-1.jpg)

.jpg)