Courtroom utilization studies are becoming an essential tool in planning courthouse facilities. These studies assess how courtrooms are used, generating data that influences decisions about the number and size of courtrooms. By understanding current usage, courts can reduce the size and cost of new or renovated facilities while improving operational efficiency.

What Are Courtroom Utilization Studies?

These studies systematically analyze how courtrooms are used. They look at how often courtrooms are in session, the types of proceedings held, the number of participants, and how long proceedings last. The data informs decisions about current and future courtroom requirements.

Key Elements of a Utilization Study

A robust study draws from several data sources:

- Caseload: Historical caseload data (preferably over 10+ years) helps forecast future workload. It’s important to evaluate both the total volume and the types of cases handled.

- Proceeding Types: Identifying the nature of proceedings—such as trials versus motion hearings—is crucial. The data is often gathered from court calendars or dockets and may require significant manual input unless maintained in an electronic database.

- Occupancy Counts: Knowing how many people are in a courtroom, and where they sit (gallery vs. well), provides insight into space utilization. Manual surveys and modern occupancy sensors (door counters or ceiling-mounted units) can be used.

- Time in Courtroom: Data on when courtrooms are active helps identify usage patterns. While some courts track this manually, systems like “For the Record” (FTR) offer timestamped recordings that enable more precise analysis.

Telling the Story with Data

The real value lies in combining these data points:

- Start with time in the courtroom to understand when it’s used.

- Overlay the types of proceedings to contextualize the usage.

- Add occupancy data to gauge how full courtrooms are during various hearings.

- Use caseload forecasts to project future demand.

This combined picture tells the full story of how courtrooms function and what will be needed going forward.

Planning for Fewer, More Efficient Courtrooms

After a comprehensive analysis, many studies reveal underutilized courtrooms—often used only 50–60% of the time with low occupancy rates. Traditionally, judges are assigned dedicated courtrooms, but this model can lead to space inefficiency.

A more modern approach is to design a suite of courtrooms tailored to proceeding types. Judges use larger courtrooms for trials and smaller ones for hearings. This flexibility allows courts to match courtroom size to function and maximize facility efficiency.

The Importance of Judicial Engagement

While data drives planning, judge feedback is critical. Judges can clarify missing data, contextualize results, and ensure that the analysis reflects actual use. It’s also important to emphasize that courtroom utilization data is not a measure of judicial performance but a planning tool to support operations.

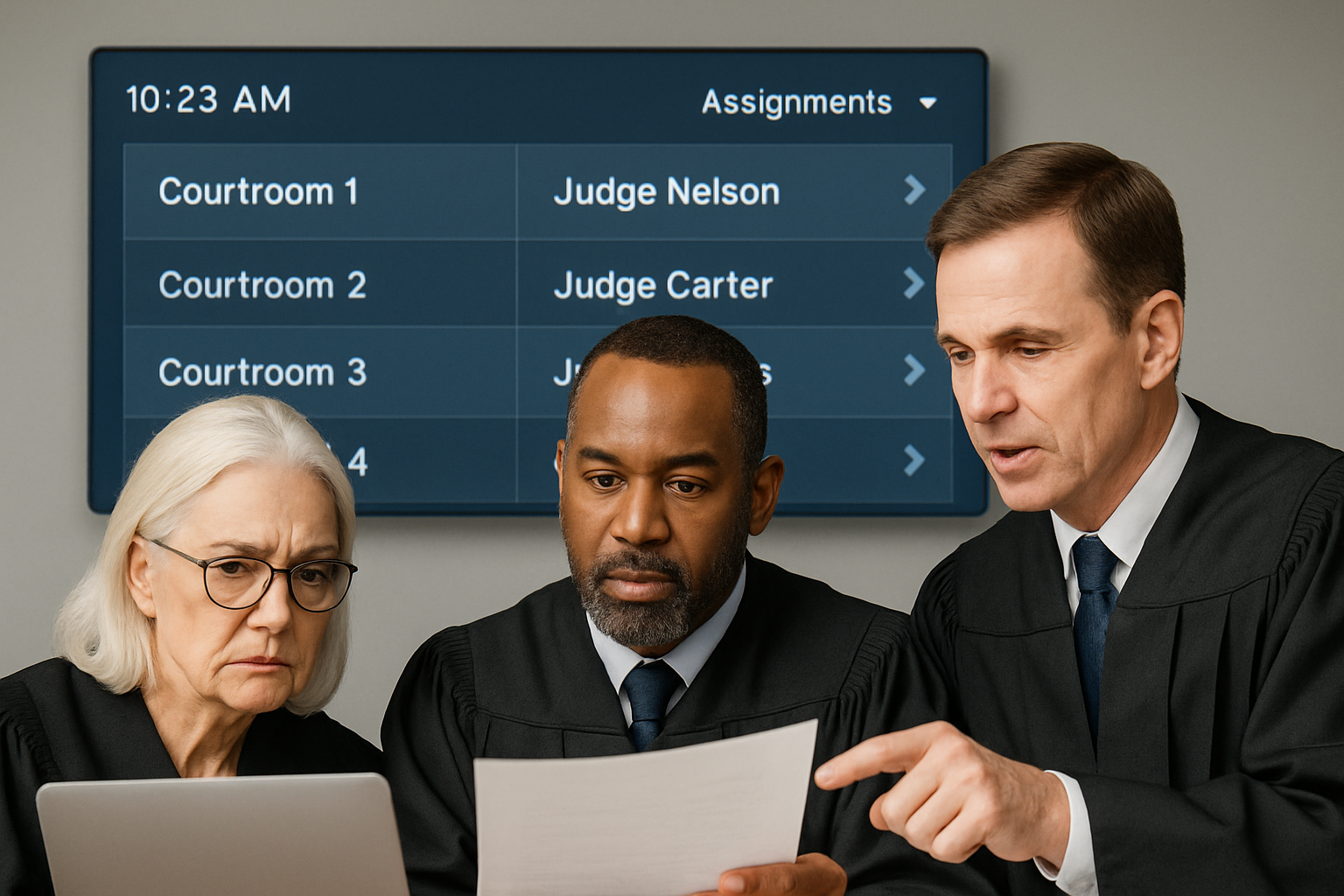

Courtroom Sharing and Scheduling

Right-sizing often means fewer courtrooms than judges, requiring shared use. This involves a cultural shift, workflow coordination, and a scheduling system to reserve courtrooms. While it adds complexity, it offers significant savings and flexibility.

Example: Space and Cost Savings

Let’s say a courthouse currently has 10 courtrooms. Six are jury-capable at approximately 1,800 square feet (SF) each, one is a large multiparty courtroom at 2,000 SF, and three are smaller courtrooms at 1,500 SF each. The total courtroom space adds up to 17,300 SF (not including ancillary spaces). Based on the utilization study, courtrooms are in use about 60% of the time, with an average occupancy of 30%.

Based on data showing a 30% occupancy rate, the courthouse could be renovated—or a new one designed—with courtroom sizes better aligned to actual use. For instance:

- 2 large courtrooms at 2,000 SF each

- 4 standard courtrooms at 1,800 SF each

- 2 small courtrooms at 1,200 SF each

- 2 hearing rooms at 900 SF each

This configuration would provide every judge with a courtroom but reduce the total courtroom space to 15,400 SF, saving 2,100 SF. Depending on the courthouse location and construction costs, this reduction could translate to approximately $1.9 million in savings.

A more aggressive scenario might reduce the number of courtrooms from ten to eight, justified by the data showing 60% usage. In this case, the layout could include:

- 2 large courtrooms at 2,000 SF each

- 3 standard courtrooms at 1,800 SF each

- 2 small courtrooms at 1,200 SF each

- 1 hearing room at 900 SF

This totals 12,700 SF, representing a space savings of 4,600 SF and an estimated cost savings of up to $4 million.

In both scenarios, courtroom sizes are tailored to proceeding types. Judges would select courtrooms based on their schedules and may move between rooms throughout the day if they have a mix of small and large proceedings. This flexible approach aligns with real usage patterns, supporting long-term operational efficiency and cost-effectiveness.

Conclusion: Building Courthouses for the Future

As a court planner, I see flexibility as the cornerstone of future courthouse design. While a dedicated courtroom per judge is convenient, modern court operations benefit from adaptable spaces. With integrated technology and smart scheduling, shared courtrooms can meet diverse needs while reducing costs.

Embracing courtroom utilization isn’t just about space—it’s about rethinking how we design and operate courthouses. A flexible, data-informed approach aligns the right courtroom to each proceeding, enhances efficiency, and builds a justice system prepared for tomorrow’s challenges.

_____________________________________________________________________________________________________________

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

-1.jpg)