One common issue I have seen during my years of courthouse analysis is the lack of secure prisoner movement into the courthouse, to the cellblock, and from the cellblock to the courtroom. This problem is more prevalent in older and historic courthouses, but it is widespread nonetheless. However, this is an issue that can be remedied. While the solution may require construction, the project may be a relatively modest effort that does not require a large-scale reconfiguration of the courthouse.

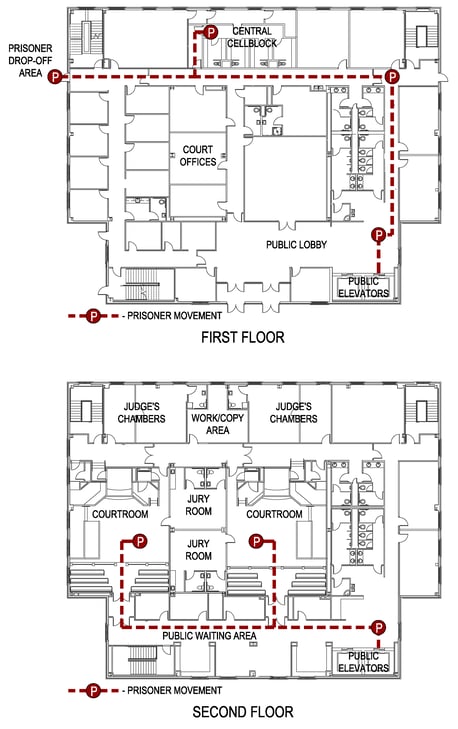

One courthouse I visited in the mid-south had virtually no special provisions for secure prisoner movement. The prisoner transport vehicle dropped prisoners outside the courthouse in the same parking areas used by judges, and the prisoners were then escorted into the building through the same door used by judges. They were then taken to the central cellblock via public corridors. When it was time to leave the cellblock and go to the courtrooms, the prisoners were again escorted through public circulation, including public elevators, to get to the second-floor courtrooms. Prisoners were also taken into the courtroom through the main public entrances.

While security personnel took steps to minimize the risk to the public, judges, and courthouse staff, that risk still existed, as did other issues – such as the potential for prisoners to be escorted past victims’ families, witnesses, and their own families.

Poor Prisoner Movement

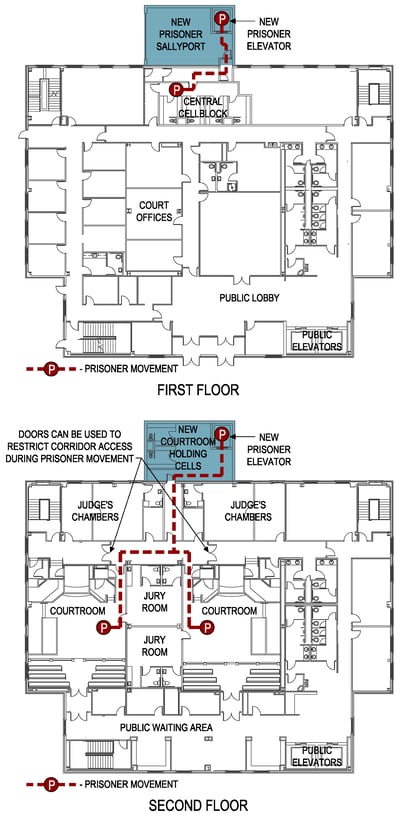

This courthouse recently underwent a construction project that added three key features to greatly improve the security of prisoner movement:

- A sallyport

- A dedicated prisoner elevator

- Courtroom holding cells

Sallyport

The lack of secure prisoner movement often starts at the entrance to the courthouse. In the case of this courthouse, unloading prisoners in the judges’ parking area created the potential for judges and prisoners to cross paths. I’ve seen other cases where prisoners would be unloaded in a public area of the parking lot or taken into the building through the main public entrance.

A prisoner sallyport can relieve this problem. A solid-walled structure with a roof is preferable, but a walled-off or fenced-off (with visual barrier) exterior area would be a cost-effective option. The important thing is to physically segregate the prisoner unloading area from other areas.

Prisoner Elevator

Ideally, the sallyport would be connected through secure circulation to the central cellblock and/or courtrooms. This may not always be feasible without a major reconfiguration. But if the courthouse stacking and layout allows, this secure connection could be made via a dedicated prisoner elevator. Some prisoner elevators are equipped with a lockable gated partition in which to securely hold prisoners while the elevator is in operation.

Courtroom Holding Cells

During recesses in court proceedings, it may not be efficient to move a prisoner from the courtroom to the central cellblock and back to the courtroom again, especially when the recess is short. Furthermore, movement of prisoners should be limited in order to minimize security risks. This is where courtroom holding cells come in. A courtroom holding cell is a cell or group of cells directly adjacent to the courtroom or easily accessible to the courtroom via secure circulation. Holding prisoners in these cells prior to or during a recess can speed up proceedings, improve security, and reduce some of the demands of security personnel.

Putting it All Together

In the example I mentioned above, the project to improve prisoner movement involved constructing a relatively small, two-story addition on the back of the building, directly behind the existing central cellblock. As seen in the floor plans below, the first floor included a vehicular sallyport large enough to hold two prisoner transport vans. The sallyport had direct and secure access to the existing central cellblock. The addition also included a prisoner elevator that led to the second floor, where two courtroom holding cells were constructed close to the existing courtrooms. To gain access from the holding cells to the courtrooms, a new corridor was constructed through an existing workroom/copy area.

The final piece of the enhanced prisoner movement required the use of the existing corridor that is also used by judges to access their courtrooms from chambers. To ensure that the paths of prisoners and judges would never cross, a portion of the corridor was sealed off by two doors that could temporarily be locked down for prisoner movement. All other times, the doors would be open, and the corridor would be free to use by the judges.

It Doesn’t Take a Major Construction Project to Make Major Improvements

The construction project outlined above was a modest-sized addition that created minimal impacts to the existing spaces and minimal disturbances to court operations during construction. Other than eliminating the workroom/copy area and some windows where the addition attached to the existing building, impacts to the existing spaces were minimal. Other courthouses may have greater impacts, and some interior alterations may be required. However, improvements of this type are more than worth the trade-offs when they result in the more secure movement of prisoners, which is critical to protect the safety of all who find themselves within the walls of a courthouse building.

___________________________________________________________

Click the image below to download our courtrooms and chambers eBook

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)