When courthouse planners, architects, or court managers consider various possibilities for the layout of a new courtroom, how far from historic norms should they expect to depart? There has been a strong thread of consistency in the form and function of American courtrooms from colonial times to the present. Is there a reason for that past consistency, and does that reason also suggest the need to continue those forms and functions into the future? This article addresses those questions by exploring the roots of American courtroom design.

Since I live on the East Coast, I have had the opportunity to spend several weekends in Colonial Williamsburg with my family, touring this fascinating and well-preserved living museum of our nation’s architectural and cultural heritage. Given that Williamsburg was founded in 1699, one would expect some differences from the American communities we live in today. But upon visiting, some things were surprisingly familiar. One of these similarities - observed through participation in a mock trial - was the function and parts of the main courtroom in the historic Williamsburg courthouse.

I have written several articles and an eBook about contemporary courtroom design. Some of these articles have addressed the variations that can occur among full-sized trial courtrooms. However, looking back at the variations described in those publications, it is interesting to note that they all fall within a form and function framework generally consistent across both time and geographic regions. So, the question arises: why is this thread consistent? Let’s look at the roots of American courtroom design based on what I discovered at Williamsburg and confirmed by subsequent research.

Looking Back Across the Pond

It should come as no surprise that, as British colonies, America had a tendency (with one notable hiccup in 1776) to actively copy the culture and institutions of the “Mother Country.” What may come as a surprise is the formality of the original requirements for replicating British legal procedures that still guide us today.

Statutes of Reception

Following the 1776 revolution, one of the first legislative acts undertaken by each of the newly independent American colonies was to enact a reception statute that adopted the existing body of British common law… to the extent that American legislation or the Constitution did not explicitly reject that body of law. Some states enacted reception statutes as legislative statutes, others adopted British common law through provisions of the state's constitution, and others adopted it by court decision.

The U.S. Constitution rejects British traditions, such as the monarchy. Still, many British common law traditions - such as habeas corpus, jury trials, and numerous other civil liberties - were adopted in America by not rejecting them. Significant elements of British common law remain in effect throughout the United States because American courts or legislatures have never rejected them.

All U.S. states have either implemented reception statutes or adopted British common law by judicial opinion, except Louisiana - where only a partial reception of British common law was combined with French and Spanish laws.

Form Follows Function

The statutes of reception established principles of British common law for use in American courts, but they did not establish courtroom forms. How did the American courtroom evolve from the British courtroom and remain essentially the same for more than three centuries? It is a matter of form the following function.

Essentially, the answer to the question: “What is the reason for the thread of consistency in the form and function of American courtrooms from colonial times to the present?” is that the consistent and relatively uniform adoption of British common law has directly led to continued consistency in the function of our courtrooms, and correspondingly, to continued consistency in the form of full-sized American trial courtrooms.

Let’s explore some of those consistent courtroom characteristics.

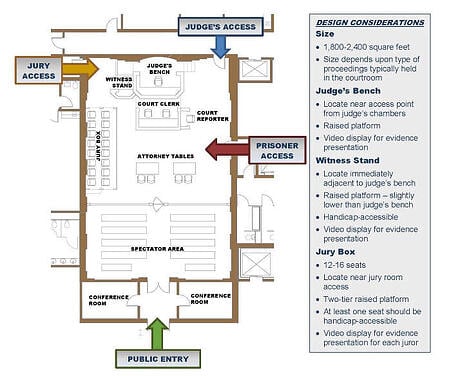

Courtroom Components

The basic principles of British common law that were adopted in America, first during colonial times and later following independence, were fundamentally based on an adversarial system that included prosecutors or plaintiffs versus defendants, representation by legal professionals (barristers or attorneys), a presiding judge or judges, a jury of peers, witnesses, and multiple court personnel for recording the proceedings and keeping order.

The courtroom components required to support the participants in this adversarial system are essentially the same in today’s American courtroom design as during colonial times and as always in British courtrooms.

These components include:

- judge’s bench

- witness stand

- court clerk, reporter, and bailiff stations

- attorney, prisoner, plaintiff, and defendant stations

- jury box

- public spectator seating area

The following plan depicts a typical arrangement in a contemporary full-sized American trial courtroom.

Courtroom Layouts

Although the individual courtroom components included in British and American courtrooms have remained consistent over the years, that does not mean that the various individual courtroom components (e.g., judge’s bench or witness stand) have been consistently located in the same place in all full-sized trial courtrooms. Using the same courtroom components can still retain the consistency of function within varied layouts.

As shown in the above photos, the location of the witness stand at the rear of the courtroom well in London’s famous Old Bailey courtroom is unlike the typical American witness stand location adjacent to the judge’s bench as depicted in the photo of the Oregon trial courtroom. However, witness stands toward the well's rear can occasionally be found in American trial courtrooms.

In addition, historic colonial courtrooms sometimes had layouts that differed from today’s contemporary courtrooms. Due to the relatively small size of many historic courthouses, the courtroom well components (including the judge’s bench, witness stand, jury box, clerk’s desk, and attorney stations) were often compressed into a smaller space than would be considered suitable for today’s trials.

American courtroom design layouts can differ geographically from courthouse to courthouse. One particular example is the placement of the judge’s bench (e.g., center, corner, or side). However, there has been a high overall continuity and consistency of courtroom components within a basic layout framework.

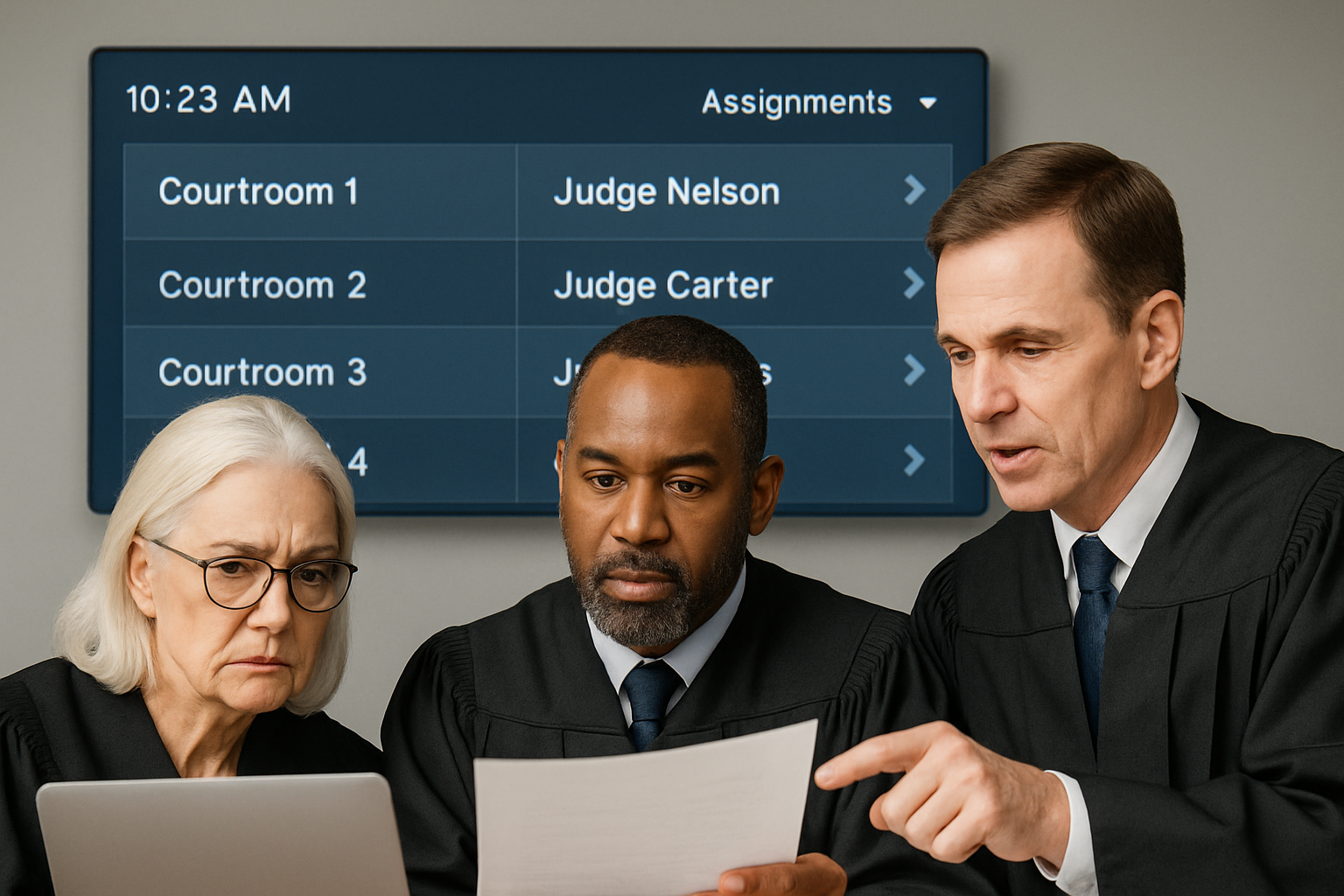

Enter Technology to American Courtroom Design

Now that I have stressed the importance of British common law as the central factor that has led to centuries of continued consistency, the digital revolution could be the change agent that could break this thread of consistency.

As with so many aspects of our lives today, technology is changing the paradigms we view the world.

We have written several articles on how technology can modify form and function in a courtroom. Most recently, the blog Videoconference Hearing Rooms described using videoconference technology to accommodate hearings conducted with a judge and defendant in separate cities. While currently mainly used for preliminary hearings, videoconferencing could accommodate remote trial participants in complete trials. Videoconferencing is used in multiple jurisdictions to connect a trial courtroom with additional courtrooms that provide overflow spectator seating. Should these changes in function become more widespread, a shift in form is likely to follow.

Final Thoughts

Now, the “sixty-four thousand dollars” question: “Does the historical reason for the thread of courtroom component and layout consistency (British common law) also suggest the need for a continuation of traditional courtroom forms and functions into the future?

In the past, there was a need to maintain consistency of courtroom components within a relatively flexible courtroom layout framework. In the future, this layout framework will become even more flexible.

When courthouse planners, architects, or court managers consider various possibilities for the layout of a new courtroom, how far from historic norms should they expect to depart? I do not have a crystal ball. However, based on the changes I have observed over the past decade, I suspect technology will allow future courtroom layouts, and perhaps even the essential courtroom components, to significantly depart from historic norms while still supporting the basic principles of British common law.

________________________________________________________

Click on the Image to Get your Trial Courtroom Download