Problem-solving courts that develop programs to successfully reintegrate parolees into the community and reduce recidivism rates have been an emerging trend in the American judicial system in recent decades. But do traditional courthouses – and the traditional courtroom layout – work for these courts? How can the courthouse better support this emerging trend during the courthouse planning process?

The Problem Defined

Criminal justice professionals have long grappled with how to increase the odds of a convicted offender’s successful return to society. This is a concern for the released offender, society at-large, and particularly for the country’s overburdened courts and prisons.

Nationwide, more than 600,000 individuals are released from state or federal prison each year, many as parolees. Many have committed drug-related or non-violent crimes. Two-thirds of those who are released have historically been re-arrested. Nearly half of that number return to prison for a new crime or a parole violation within three years, which continues to add to the growing issue of overcrowding in U.S. prisons.

Problem-Solving Courts: A Potential Solution?

In recent years, the criminal justice community has introduced problem-solving courts as a more focused way to address the individual requirements for a parolee’s successful re-entry into society. Nearly 4,000 problem-solving courts have now been established in the U.S. at the state and federal levels. These courts are based on the premise that some offenders are more likely to succeed by addressing the underlying problems leading to their criminal behavior rather than taking a more punitive approach. Issues such as unemployment, substance abuse, housing, mental health issues, and the lack of education may be explored and addressed.

I recently spoke with the chief judge of a large court in the Pacific Northwest about her jurisdiction’s experimental problem-solving court program. She called it a ground-breaking model that would combat recidivism related to the explosive growth in methamphetamine abuse and trafficking in the region. Describing it as the new cornerstone of the court’s approach to justice, she assured me that she intended to promote its use even in neighboring jurisdictions.

Problem Solving Courts: How they Work

Once an offender is approved for parole, the individual may elect to be released through a problem-solving court, which conducts judicially supervised, non-adversarial proceedings. Multi-disciplinary teams are involved in the hearing. In addition to the judge, these teams may include prosecutors, defense attorneys, parole officers, mental health and substance abuse counselors, and other community treatment providers. The programs offer supportive incentives and treatment options, as well as sanction alternatives.

Offenders who successfully complete the program and integrate back into society often report that their success is largely attributable to the development of interpersonal relationships with the judge and treatment team. The positive feedback and incentives they receive for meeting goals established by the program have also proven to be effective. In short, problem-solving courts give paroled offenders the tools they need to succeed.

Problem Solving Courts - Supportive Courtroom Design

But how well does the traditional courtroom – typically a formally appointed room intended to convey a sense of dignity and decorum – support the concept of problem-solving courts? And if a formal courtroom layout isn’t conducive to this new type of proceeding, how can courthouses respond to this need?

Proponents of problem-solving courts have argued that the courtroom itself serves as a vital therapeutic instrument. The overall impression of a courtroom used for problem-solving proceedings should be different than a courtroom used for more traditional proceedings. The layout should convey the message that offenders are included in the process and that all participants are working together to achieve a common goal. As the concept of problem-solving courts expands, it is inevitable that more specially designed courtrooms will be developed to support these proceedings.

Following are some design considerations for problem-solving courtrooms.

- Larger than normal spectator seating area

A key principle of the problem-solving court is for offenders to observe the proceedings of other individuals to witness first-hand both the successes and failures of their peers. Therefore, larger than normal spectator numbers may be expected, and the seating area should comfortably accommodate all spectators – offenders and the multiple parties involved in the proceedings.

- A more relational design

Because problem-solving courts are intended to be non-adversarial proceedings that emphasize accountability, treatment, and dialogue among the participants, they should be designed to be more relational than traditional courtrooms. For example, the elevated height of the judge’s bench might be reduced to make the judge appear more approachable and participatory, or the judge might sit among the other court representatives to convey the message that all participants are on the same team.

Judges’ Bench in Problem-Solving Court

Furthermore, to help ease the anxiety of offenders, ceiling heights could be lower than in the traditional courtroom. Also, a less formal décor, such as fabric wall coverings instead of wood-paneled walls, could be used.

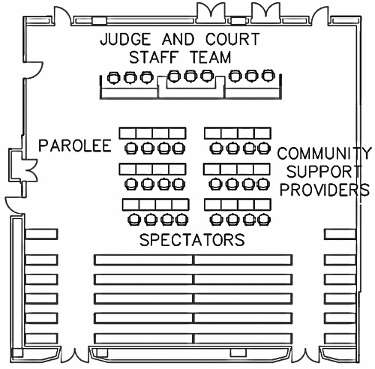

- Modified well area

Traditional courtroom design typically allows for space to accommodate one table for the prosecution and one table for the defense. For problem-solving courts, the treatment team is often expansive and can include participants from several court components and community groups. The courtroom well should accommodate all key players who participate in the proceedings. On the other hand, standard trial courtroom elements, such as a witness stand and jury box, would not be required. Following is an image of how a courtroom could be designed to accommodate a problem-solving court.

Problem-Solving Courtroom Layout

It may be possible for a court jurisdiction to designate a particular courtroom for problem-solving court proceedings or, if that is not possible, to make use of a flexible layout with furniture that may be relocated to accommodate both traditional and problem-solving court proceedings. As the problem-solving court model continues to expand, it will be increasingly important to establish standard ways for courtroom design to more effectively align with the mission of this unique type of court.

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

-1.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)